Financial Independence Number: Definition and How to Customize

The financial independence number is a benchmark to determine retirement preparedness. It’s also known as the FI number.

The financial independence number is a benchmark to determine retirement preparedness. It’s also known as the FI number.

Financial independence is achieved by:

- building enough passive income to cover annual expenses, or

- amassing a lump sum of enough savings and investments to cover living expenses through withdrawals, or

- a combination of #1 and #2.

The financial independence number is the target lump sum. Calculating the amount answers the question, how much money do I need to stop working full-time?

Though not perfect or set in stone, there are years of data and research behind using this single number to help determine the long-term viability of a retirement nest egg.

The financial independence number works fine as a baseline guidepost, but most people should tweak it to optimize long-term objectives and plan conservatively in preparation for the unexpected.

This article explains the origins of the financial independence number, how to calculate it, and ways to customize it for your planning purposes.

Table of Contents

Origins of the Financial Independence Number

The origins of the financial independence number go back to the 1990s and the work of an advisor named William Bengen. Later, three professors at Trinity University published a paper about safe retirement withdrawal rates building on Bengen’s analysis.

The three professors looked at stock and bond data from 1925 to 1975. They concluded that a retiree could safely withdraw 4% of their total assets per year over any thirty years during that period without running out of money.

For example, if someone entered retirement with $1.5 million of invested assets, they could withdraw $60,000 per year for living expenses for the next 30 years. The person would have a >98% chance of a solvent retirement.

The paper became known as the Trinity Study, and its conclusion is the basis for the 4% rule of thumb, which we use to calculate the financial independence number.

If history is any guide for the future, then withdrawal rates of 3% and 4% are extremely unlikely to exhaust any portfolio of stocks and bonds during any of the payout periods (from 1925 to 1995).

The 4% rule of thumb has become a crucial retirement planning tool for advisors and individual investors.

Analysts have replicated the study many times since, using updated data and coming to similar conclusions. An advisor and influential blogger named Michael Kitces is one of the more prominent modern researchers.

His recent appearance on the Bigger Pockets Money Podcast is an excellent overview of the 4% rule of thumb and other planning strategies.

How to Calculate Your Financial Independence Number

The financial independence number equals annual household spending divided by 4%.

This formula serves as the baseline, but most people should consider adjusting the number for their personal situation.

To calculate the number, first determine annual spending. Count total expenditures for the year or average monthly expenses. Be sure to add estimated post-employment healthcare expenses since employer benefits will cease in retirement.

I prefer to use bank account data and a spreadsheet to calculate annual expenses using Excel pivot tables.

You can also use a free automated tool like Mint.com or Empower to track spending automatically.

Once you have the annual spending number, divide it by 4% (0.04). Or multiple your annual spending by 25. Either way works.

The total is the financial independence number.

We’ll use $75,000 annual spending in the examples throughout this post.

= 75,000 / .04 = $1,875,000 = 75,000 * 25 = $1,875,000

Another way is to take your average monthly spending and multiple it by 300 (12*25)

= 6,250 * 300 = $1,875,000

The goal is to save this total lump sum by aggregating all investments, savings accounts, and other investment equity. Once you’ve hit the number, you’ve reached financial independence.

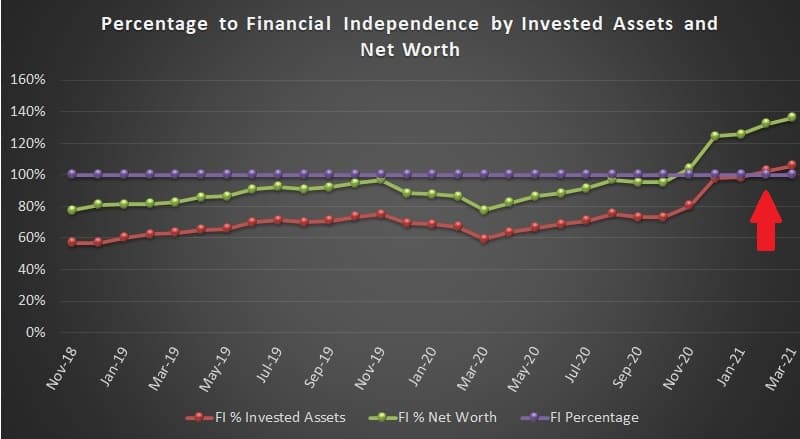

Use it as a wealth-building measuring tool to track your invested assets as a percentage of your financial independence number (see chart at the bottom).

But do not consider the financial independence number as an absolute end goal because there are many other factors to consider.

What are Invested Assets?

Total invested assets is different than net worth.

Some people calculate their net worth and use that to measure progress toward financial independence. That’s easier but less accurate.

Remember, the goal is to build a lump sum of savings and investments (or “invested assets”) equal to the financial independence number.

For a better picture, exclude the equity value of your primary residence and other non-retirement funds such as college savings accounts.

Do include the value of equity in investment real estate properties or other assets you can liquidate to buy other income-producing assets.

Furthermore, suppose you generate after-tax income from stocks, bonds, or real estate investments. In that case, you may choose to exclude the underlying assets from your invested assets calculation and reduce your financial independence number — more on that below.

How to Customize Your Financial Independence Number

One of the more notable takeaways about the 4% rule of thumb from the earlier-mentioned podcast with Michael Kitces is:

- there’s a 50% chance the retiree will end up with almost 3X the original savings

- there’s a 96% chance the retiree will end up where they started 30 years prior

- there’s about a 1% chance of ending up with zero.

That means the 4% rule of thumb is a conservative benchmark meant for the most risk-averse.

Those willing to accept more risk can withdraw a bit more, say 4.5%, and still have a good chance of maintaining retirement security for 30 years.

That said, 4% may be too risky for early retirees.

The 4% rule works over 30 years. For someone in their 60s, it’s likely to last the rest of their lives.

But for early retirees in their 30s, 40s, or 50s, 30 years may not be a sufficient planning horizon.

Thus, a more conservative 3%-3.5% withdrawal rate may be more appropriate for those with a longer life expectancy or who want to leave a financial legacy.

Reducing the withdrawal rate is one of the most effective ways to reduce risk.

Another way is to reduce annual spending.

There are other ways to customize your financial independence number by accounting for additional income or income-producing assets.

I’ve written specifically about how I measure progress toward financial independence using the F12MII number from my Portfolio. Below is a more general description of how to modify the number.

Adjustment for Additional Income

People sometimes overestimate how much they need to retire and keep working a job they don’t love.

If you expect to receive income after retirement, you can reduce your financial independence number and bump up your retirement date.

The most obvious additional income stream in the U.S. is Social Security. Younger folks like to plan for retirement without Social Security because of doubts it will exist.

That’s an unlikely scenario.

Despite politics and deficits, all Americans should expect to receive Social Security when they reach retirement age.

For example, if you expect to receive $2,000 per month in Social Security benefits at a certain age, that’s $24,000 per year.

Using the previous example of $75,000 in annual expenses, you can now calculate your financial independence number using an adjusted spending basis. The additional income covers a portion of the spending.

= (75,000-24,000) = $51,000 * 25 = $1,275,000

In this example, we’ve reduced the financial independence number by $600,000, down from $1,875,000.

That shaves off several years of work if you follow the 4% rule of thumb and don’t mind relying on the government as part of your plan.

The lesson here is that a little bit of additional income goes a long way.

This kind of adjustment works well for Social Security, pensions, and earned income (part-time work) because there’s no underlying invested capital generating the income.

Invested capital that produces income is a bit different.

Adjustment for Income-Producing Assets

When I write about income-producing assets and building income streams, I’m usually referring to investments that create passive income. These investments include dividend stocks, bonds, traditional and crowdfunded real estate, certain business income, and other savings.

If you adjust the financial independence number down due to income-producing assets, you should consider subtracting the underlying asset amount from the pool of available safe withdrawal assets.

For example, let’s say you have a $200,000 taxable dividend growth account that yields 3.0% and generates $6,000 in annual income before tax. You can reduce the basis of your yearly expenses by $6,000, thus lowering your financial independence number by $150,000 (= 6000 * 25).

The $200,000 should not be included in your total invested assets aggregation if you reduce the financial independence number.

Here’s a side-by-side comparison building on our previous example. The first is calculating the financial independence number without adjustments. The second adjusts for the dividend portfolio.

We’ll assume the investor has $1,000,000 of invested assets.

Annual spending = $75,000 Financial independence number = $1,875,000 Total invested assets = $1,000,000 Percentage to financial independence = 53.33%

Annual spending = $75,000 Financial independence number basis = $1,875,000 Total invested assets = $1,000,000 Dividend portfolio value = $200,000 Adjusted invested assets = $800,000 Dividend income (before tax) = $6,000 Adjusted annual spending = $69,000 Adjusted financial independence number = $1,725,000 Percentage to financial independence = 46.37%

The second example shows slower progress as measured by the percentage of financial independence.

So why reduce the financial independence number by $150,000 when you could be $200,000 closer to your initial target? What’s the benefit of making this more complicated?

For planning purposes, you can do it either way. But most of us are more concerned about a secure retirement than a more imminent one.

Using this method accounts for assets we don’t plan to liquidate.

Building and maintaining sustainable income streams will help to prolong retirement security without the sole reliance on withdrawals.

Reliable income is vital for early retirees to help sustain extended retirement periods. It can also help fund long-term health expenses, support family members in need, and maintain wealth to leave a financial legacy to family or charities.

Conclusion

Years ago, when I set a goal to retire at age 55, I expected that I’d be able to generate enough passive income from dividend stocks to fund my retirement lifestyle.

Now that I’m 45 and my retirement account balances have soared, I can retire sooner by using a hybrid approach to funding my retirement.

I’ll rely on both sustainable income from dividends and real estate, and I’ll tap my tax-advantaged accounts when I reach age 59 1/2.

Since this realization, I’ve customized my financial independence number to account for income-producing assets that I don’t intend to liquidate. The extra calculation complicates the equation a bit instead of just using 25x annual spending.

But it serves me better, giving me a thorough picture of what I need to accomplish to reach F.I.B.E.R.

Below is a chart that I’ve been plotting since November 2018. It shows my net worth (green) and invested assets (red) as a percentage of my financial independence number (purple line).

I calculate my annual expenses for the calendar year. In February 2021, I reached financial independence.

The goal is to KEEP the red line above the purple line and grow the spread between them until I retire.

The wider the spread between red and purple, the more secure and comfortable my retirement will be. It will also increase my chances of leaving a financial legacy to my family.

Featured photo via DepositPhotos used under license.

Featured photo via DepositPhotos used under license.

Craig is a former IT professional who left his 19-year career to be a full-time finance writer. A DIY investor since 1995, he started Retire Before Dad in 2013 as a creative outlet to share his investment portfolios. Craig studied Finance at Michigan State University and lives in Northern Virginia with his wife and three children. Read more.

Favorite tools and investment services right now:

Sure Dividend — A reliable stock newsletter for DIY retirement investors. (review)

Fundrise — Simple real estate and venture capital investing for as little as $10. (review)

NewRetirement — Spreadsheets are insufficient. Get serious about planning for retirement. (review)

M1 Finance — A top online broker for long-term investors and dividend reinvestment. (review)

This is a fascinating read! I’ve always been quite averse choosing a retirement ‘number’ (I’d rather have an age in mind / a lifestyle goal), but this has definitely made it possible to combine the hazier goals I’ve already got with a clearer retirement number. Your post has done very well in showing us the numbers and how to make it an easy calculation – something that I really appreciate considering my strengths in humanities rather than science.

With the 4% rule, has the recent pandemic changed your opinion on how reliable it is? I know it’s a bit of an unfair question as the stock market has recovered rapidly quickly – but it also wasn’t guaranteed to do so. Would you change the number up slightly to prepare for issues?

I really enjoyed reading this post and I think that I’ll have to create an excel spreadsheet to figure this out for myself overtime (my expenses are likely to change dramatically over the coming years, and so I’m hoping I can automate that…). I think it’d also be interesting to factor in the UK pension scheme, I believe that you’re given a set amount to take out each week (which would be classed as passive income), but it’s a pretty complex system so I’d definitely need to do some thinking.

Sorry for a slightly rambling response – but I enjoyed this post and it’s definitely given me food for thought!

TARI,

Thanks for the comments. I started with my retirement age too. What I realized a while back though, is I need to know if I can retire at the age, instead of just stop when I get there. I’ll be much more comfortable if I have some data to support my retirement preparedness. Hence that chart at the end of the post. Five years from now, I expect I’ll be above the purple line.

The pandemic hasn’t really changed my view or planning. But I’m not someone who’s going to hit the financial independence I number and retire the next day. I will be conservative. This could include paying off my mortgage to lower annual expenses, and continuing my online business endeavors into retirement to have that additional income. Come to think of it, I don’t include my business income in my financial independence number, but I do include the estimated liquidation value of my business. If I did it the other way, I’m probably much closer to FI. But I’m not looking to “retire” to become a full-time blogger. It’s too much work, even though I enjoy it.

-RBD

Have always loved your articles RBD! With your new view, what will you be looking to retire?

Thanks Andrew. The plan hasn’t changed. I am still planning to fully retire at age 55, which is about ten years from now. But I would love to bump that up by five years. Healthcare and college costs for my family are too very big factors that may prevent the earlier date, plus I have an excellent full-time gig right now. But I may be able to retire from my full-time career and focus more on entrepreneurship before 2030. I need to maximize my current income and keep building passive income streams. I’d like to see where we are after the pandemic and recession which should paint a better picture of where I stand.

I like what you’re doing on YouTube. Good stuff.

Cool read, and nice explanation of how you calculate financial independence number and percentage achieved.

One thing I would also do is make sure the (adjusted) invested assets number only includes accounts that are fair-game for using in retirement to withdraw from and cover ongoing annual spending. For example, in my situation I would deduct 529 accounts as those will be liquidated to cover college for the kids.

Some savers may have a lot of their invested assets in tax deferred accounts. Isn’t an adjustment for taxes upon withdrawal necessary when calculating your financial independence number. Thoughts?

The research that concluded with the 4% rule of thumb accounted for taxes and several other assumptions. So for planning purposes using the rule, you don’t need to adjust. If you’re modifying the number as I do, you can account for taxes. I left taxes out of my calculations to simplify the article. The other article I linked to about how I specifically measure progress toward financial independence does account for taxes.