When to Fire (or Hire) a Financial Advisor

I’m a DIY financial planner and investor.

I’m a DIY financial planner and investor.

Hiring a financial advisor never made sense since I studied finance and enjoy money management as a hobby.

I almost became an investment advisor a few times.

My financial situation has never been that complicated. I keep my investments, taxes, and personal finance activities within my capabilities, so I don’t have to hire anyone.

Most adults are capable of managing their money themselves, and most do. Only 38% of adults over age 50 have used a financial professional to help plan for retirement, according to a recent survey by AARP.

Though I side with the DIY crowd, financial advisors play an essential role.

My parent’s retirement accounts have been with an investment advisor for the past 20 years.

But the time has come for them to part ways. It’s a decision my Dad took very seriously.

So why did they fire their investment manager after all these years?

Table of Contents

Building a Security Blanket

My parents retired around 2003 with a modest 403(b) and IRA.

A teacher’s pension and Social Security would be enough to fund a comfortable retirement lifestyle.

Dad chose the pension option that paid him until the end of his life. If he dies first, there will be no continued pension income for my Mom.

So, the purpose of their retirement accounts is to provide financial security for my Mom if my Dad dies first.

The only withdrawals they’ve made were required minimum distributions (RMDs) for the last seven years.

He found a money manager through a group of retired teacher friends soon after retirement. I was traveling at the time and didn’t provide input on the decision. I’m doubtful my input would have been helpful as my mind was elsewhere.

The accounts have grown significantly since 2003 but underperformed the market.

That’s to be expected because it’s an age-adjusted protective portfolio allocated to no more than 50-70% stocks over the years. The portfolio was always slanted toward wealth preservation.

My parent’s advisor ultimately grew the portfolio and protected against downside loss, successfully navigating the occasional crises over the past two decades. But the service was costly.

My Dad was comfortable with the advisor for more than a decade. But as he learned more (and read many of my articles), he started questioning the investment strategies.

I didn’t pay much attention because it wasn’t my money and he could handle it — until a disruptive health event got me more involved.

The Meeting

After the health event, my Dad started to worry about his finances and Mom’s financial security if he were to pass. He became more skeptical of his advisor and asked me to pay closer attention.

I became a power of attorney on the accounts, and we set up a conversation between me and his advisor.

I’ve had lots of conversations with financial advisors. I even interned for one and decided against that career path.

My intern boss was non-transparent with how he made money, telling me about fees, “The client never sees it.”

This sleight-of-hand fee was built into the business operations of a very large advisory firm (that didn’t pay interns), making me uncomfortable.

It’s one thing to be on that side of the wall. But when it’s your family paying fees, you want to see and understand them.

I reviewed my Dad’s portfolio and recent transactions before the phone call.

My parent’s advisor was transparent about his AUM (assets under management) fee, which hovered around 1.3% over the years. But that’s not the extent.

The portfolio was full of managed mutual funds, with expense ratios averaging about 0.80%.

Combined with the 1.3% AUM, my parent’s portfolios were handicapped to underperform their investment objective by 2.1%. The advisor agreed.

The advisor had recently sold a few index ETFs, like the IWM (iShares Russell 2000 ETF), and bought several managed mutual funds. I knew one of the stock funds to be a chronic underperformer (from my previous employer’s lousy 401(k)).

I won’t mention the fund administrator, but they are notorious for selling loaded funds with 12b-1 fees (“marketing fees” paid to advisors).

I asked why he sold the index funds in favor of the managed mutual funds. He said it was because he believed they would outperform the market.

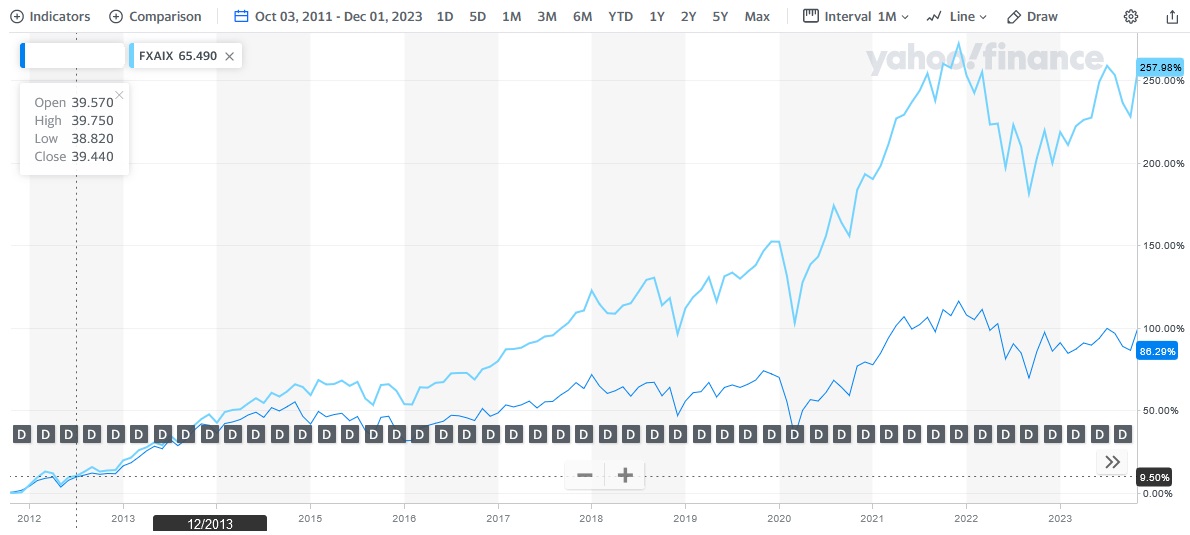

The stock funds in question had historically underperformed the S&P 500 (FXAIX below), and it wasn’t even close.

To say he believed they would outperform in the future seemed disingenuous. I wonder if his firm wanted him to invest this way, the fund administrator was paying him, or if he really believed the fund performance would change course.

This is when it became clear to me that my parents should fire their financial advisor. My Dad felt the service wasn’t worth 2% a year, and the portfolio struggled to participate in bull markets.

In recent years, his advisor stopped calling to check in.

But it would be a few more years until we actually made the move. We didn’t feel it was an emergency, so we waited for the right time.

My Dad and I will be setting up a conservative, low-fee, age-appropriate portfolio this weekend.

Reasons to Fire a Financial Advisor

You care more about your retirement nest egg than anyone else, so you should have a natural propensity to question your advisor’s strategy and investment choices.

Not everyone does. Clients who ask the fewest questions are probably the most desirable.

But blind trust is costly. Here are some signs it may be time to fire your financial advisor.

Bad Advice

Whether it’s investment, tax, insurance, or other financial advice, it’s unwise to accept the advice of a financial advisor unquestioningly.

Aim to make informed decisions in partnership with your advisor and verify the accuracy of crucial financial maneuvers via independent sources.

Ideally, verify against authoritative websites such as the IRS, FINRA, FDIC, the SEC, or other government agencies. Research portfolio holdings where the fees are clear to understand.

When Googling financial questions, don’t rely solely on the top article in a Google search. Poke around multiple sites to verify the information is accurate.

Trust your research. If you find advice given by an advisor is erroneous, speak up, get a second opinion, or consider a new advisor.

Incalculable Fees

Understand the fees you are paying for the service provided.

This includes AUM fees, commissions, or any “manufactured product” fees (e.g., complex annuities, insurance investment products).

If you can’t identify the fees you pay to the penny, ask for an explanation.

I’d ask for an annual fee report.

How, specifically, does the advisor pay themselves? When did the money come out? What positions were sold or modified to cover compensation?

If fees are in any way obfuscated, ask questions until they are not. If the problem persists or they can’t explain, I’d find a more transparent advisor or manage it myself.

Lousy Funds, Loads, 12b-1 Fees

Monitor the portfolio designed by your investment manager. Ask questions about how they’re allocating funds.

Independently analyze the fees behind the mutual funds or ETFs being used.

First, look at the expense ratio, which should be under 0.50%. Ideally, under 0.10% for most stock and bond index funds and a bit higher for more specialized funds (e.g., international bond funds).

Question your advisor’s use of managed mutual funds versus index funds. What are their selection criteria for a specific high-expense-ratio holding, and why is it better than an index fund or ETF?

Sniff out loads and 12b-1 fees. These are turds in your lawn.

Ask directly if your advisor is receiving compensation for funds. Compare after-fee performance against a broad index fund.

Even if there are no loads or 12b-1 fees, the higher-ups in the firm may be pushing certain funds over others. That’s what I suspect happened with my parent’s accounts.

When I was an intern back in the day, mutual fund companies would come to the office, bring lunch, and present their funds. It was a scratch-your-back kind of business in 1997. I hope it’s changed since then.

There’s no harm in asking for lower-fee funds. If the advisor is not open to modifications to your liking, consider other options.

Activities Contrary to the Client’s Best Interests

The first question I asked my Dad’s advisor was if he was a fiduciary, meaning he was legally required to act in his client’s best interest.

He said yes, but I should have further verified his credentials before I asked that question.

Because, in hindsight, his answer should have been more nuanced based on his qualifications.

The fiduciary standard is different than the suitability standard. Being a fiduciary is more complex than asking, which doesn’t mean an advisor will always act in your best interests.

Bernie Madoff was a fiduciary.

When you hire a financial advisor, you must navigate the “minutiae of industry terms and regulations” (see above link) to fully understand who your financial advisor is and how they are compensated.

If your advisor is not clearly acting in your best interests (by selecting bad funds, giving bad advice, or selling lousy products), it may be time to move on.

Mistakes happen, but dishonest behavior is habitual.

Mixing Insurance Products and Investments

Keep insurance and investing separate.

When you need life insurance, buy a term policy from a reputable company or broker.

To invest for retirement, build a tax-advantaged investment portfolio in a 401(k) or IRA.

Financial advisors and other salespeople sometimes recommend combining the two financial needs into one product. These policies are called:

- cash-value life insurance

- whole life insurance

- universal life insurance

- variable life insurance

- variable universal life insurance

- variable annuities

- equity-indexed annuities

- deferred fixed annuities

No matter how smart or tax-efficient an advisor or insurance salesperson says these products are, combining insurance and investing introduces complexity.

Complexity is a trap door for fees.

I defer this topic to The White Coat Investor (where I got the bulleted list), who has seen it all and fought against shitty products for more than a decade.

An advisor recommending these products is grounds for firing.

Frequent Portfolio Modifications

Once a portfolio is established, it should only require minor tweaks and annual maintenance. Trade commissions and frequent unjustified portfolio changes during the year are a red flag.

Over-tinkering introduces human emotion to a portfolio, whether it’s you or a professional. We hire advisors to avoid our own biases. Clients don’t need someone else’s biases to hurt their portfolios.

My parent’s advisor would tinker back and forth with gold and silver ETFs depending on what he (or his firm’s Chief Investment Advisor) thought the market would do. He’d modify the stocks-to-bonds ratio based on market movements throughout the year.

He never nailed it. The portfolio lagged its target objective before fees, then 2.1% worse after fees.

Frequent changes may give the impression the advisor is engaged with your account. A well-balanced portfolio with a long-term investment horizon should mostly stay the same year-to-year.

Even the best advisors can’t time the market with consistent accuracy.

Stock Picking

Investment advisors should not use individual stocks to build a client portfolio.

If the client requests certain stocks, that’s fine.

However, most financial advisors are not trained stock analysts. They spend much of their time on sales and customer relationships, not stock research.

Their guesses are likely as good as yours or mine.

Internal firm-wide stock analysts may offer some picks for advisors to consider. But I would expect to use them sparingly for speculation upon client approval.

Frequently Firm Changes and Disputes

Another red flag is frequent firm changes or client disputes.

Many investment advisors change firms throughout their careers. They’ll ask clients to accompany them, requiring paperwork and moving accounts.

This happened once to my parent’s account in 20 years when their advisor switched firms. It wasn’t a big deal, but it meant moving to a new online account and signing documents.

If that happens more frequently, asking why is valid due diligence.

The SEC has a website where you can check the history of brokers’ activities, including firm changes and “disclosures”, such as client disputes.

I looked up my internship boss, and he’s moved many times and has three significant disputes on his record. It doesn’t surprise me; he was unimpressive as an investment manager and mostly focused on sales.

I’ve also looked up several advisor friends who I know personally to be ethical and trustworthy, and their profiles have zero disputes and limited movements.

Look up your advisor. Ask about disputes and frequent firm changes. Don’t automatically switch firms if your advisor moves. Consider all options.

They Stop Calling

While my Dad was already considering leaving his advisor, his guy stopped periodic check-in calls.

In the early days, he called every quarter or six months. But not anymore. My Dad would have to initiate the outreach to get advice or learn about the current portfolio holdings.

My parents aren’t whales.

So, I suspect most of the attention went to the most prominent clients or bringing in new ones.

Personal attention and trust are a big part of why people choose and stick with a financial advisor.

If that disappears, the only factor is portfolio performance.

When my Dad told his advisor he was moving his money elsewhere, he responded with grace and a willingness to ensure a smooth transition.

Perhaps he knew the relationship was due to end.

Reasons to Hire a Financial Advisor

Most people can manage their own investment portfolio with knowledge and confidence. It doesn’t have to be complicated.

We have more financial tools at our disposal than ever before. An employer-sponsored plan, or commission-free online brokers with popular index funds and ETFs are the only tools needed to get started investing.

A simple portfolio of three to five index ETFs can do the job, even for people with multi-million dollar investment portfolios.

That said, not everyone wants to manage their money. As the dollar amounts grow larger, people become more fearful of bad investments and may prefer someone to trust (or blame) other than themselves.

Good advisors implement solid risk management plans. Clients will sacrifice some returns for safety, as my parents did. That’s a fair tradeoff most clients embrace.

Self-managing investors tend to be more willing to take risks. If the investment horizon is long, that’s OK. But when the portfolio needs to be protected to cover near-term expenses, that’s where a cautious advisor can shine.

What scenarios would make sense to hire a financial advisor?

Desire to Outsource Your Investment Portfolio

Some people don’t want the hassle of managing an investment portfolio, no matter how knowledgeable they are.

Like lawn care, house cleaning, and taxes, at some point we want to outsource required activities to save time and brainpower.

Investing, however, is a particularly costly thing to outsource as your assets grow.

A 1% annual AUM fee is the likely minimum for a full-service investment advisor or $10,000 for every $1 million. That doesn’t include expense ratios or other product fees.

As your portfolio grows, the fee becomes larger. Weigh the management cost against the effort to learn and manage it yourself. Your needs may vary at different times of your life.

Some larger mutual fund providers will manage your money for less, but your experience will be less personal.

Vanguard, for example, charges just 0.30% for advisors. My in-laws use a Vanguard advisor and have been pleased. Fidelity and Schwab may have similar services with various pricing tiers.

If hiring an advisor gives you peace of mind so you can focus on other endeavors, it may be a good option. Know the costs before signing up.

Feeling Helpless

Fear drives many financial decisions and behaviors. Some people avoid investing because they fear making an investment mistake.

The biggest mistake you can make is not investing at all. So, if an advisor helps to get your money invested, it’s better than not investing.

Unfortunately, fear makes us susceptible. Untrustworthy and predatory advisors selling lousy products and services are out there. Fully vet anyone you consider working with, and don’t rely solely on a friend’s recommendation.

Consider a fee-only fiduciary advisor to get a financial plan in place before seeking investment advice.

Even if you feel helpless when it comes to investing, you still need to pay attention while under professional management.

Significant Investable Assets

Most experienced investment advisors are not interested in small accounts.

Junior associates may be interested, but lack experience in varying market conditions. Don’t take a risk on a hungry first-year associate.

Once you hit the $100,000, self-managing that amount can be stressful. Mistakes get more costly, and a good advisor will prioritize mistake avoidance over trying to beat the market.

Start with a fee-only fiduciary advisor to get a financial plan and investment advice. Then manage the money yourself.

If you can get to $100,000, $200,000 and $1 million will be within reach sooner than you think. But the strategy shouldn’t change much until you’ve reached retirement and you’re living off of savings.

Find more substantial help when the numbers get too big and uncomfortable.

You are Super Wealthy

The richest people in the world don’t manage their own money. They pay a hefty price for full-service management.

But for the super-wealthy, the enormous fees are worth it because they offload significant responsibility. And they can afford it.

I’ll probably never be wealthy enough to want to hire someone to manage my money. But somewhere between today’s net worth and $100 million, I’d probably seek some help.

Photo via DepositPhotos used under license.

Craig is a former IT professional who left his 19-year career to be a full-time finance writer. A DIY investor since 1995, he started Retire Before Dad in 2013 as a creative outlet to share his investment portfolios. Craig studied Finance at Michigan State University and lives in Northern Virginia with his wife and three children. Read more.

Favorite tools and investment services right now:

Sure Dividend — A reliable stock newsletter for DIY retirement investors. (review)

Fundrise — Simple real estate and venture capital investing for as little as $10. (review)

NewRetirement — Spreadsheets are insufficient. Get serious about planning for retirement. (review)

M1 Finance — A top online broker for long-term investors and dividend reinvestment. (review)

Thanks, Craig. One of your best articles and advice. Thanks for sharing some personal experiences with your parents and In-laws.

Thank you. We’re going through this as I write. But it’s been a long time coming. Once we’re settled in the new account, the main annual activities will be the annual RMDs and rebalancing. This is kind of stressful for my Dad, so I’m glad I’m there to help him.